Last month, when England’s Ben Stokes announced his retirement from one-day internationals, his message was clear and clear: “The three formats are just untenable… because of the schedule and what is expected of us (the players).”

New Zealand’s Trent Boult, the latest all-format player to join the growing list of players moving away from international cricket, didn’t say it outright but did highlight the need to spend more time with his wife and kids. “Family has always been the biggest motivator for me and I feel comfortable putting it first and preparing myself for life after cricket.”

Last December, South Africa’s Quinton de Kock also expressed a desire for more family time when he retired from Test cricket at the age of 29.

They have all been victims of the overly hectic schedule of cricket which keeps the players away from home for long hours and not enough free time.

Sample India’s whirlwind schedule since the 2022 Indian Premier League (IPL) final on May 29:

In just 72 days, the Indian cricket team has had 26 match days – that is, one match every third day.

Let’s expand it.

A typical year has 365 days, which are further divided into 52 weeks. Let’s say two vacation days per week, there are about 261 active days in a year (when a person is active for the purpose of doing his job). Then there are holidays and paid leaves. After subtracting these, an average person is likely to be active for about 220-30 days in a year.

Active days for office goers usually include a combination of reading, writing, planning, meetings, phone calls, and other non-physical tasks. An average office goer has to go through the most difficult form of physical labor traveling between home and office. What modern day international cricketers do with their bodies to prepare for their main job, i.e. playing matches, will make your jaw drop.

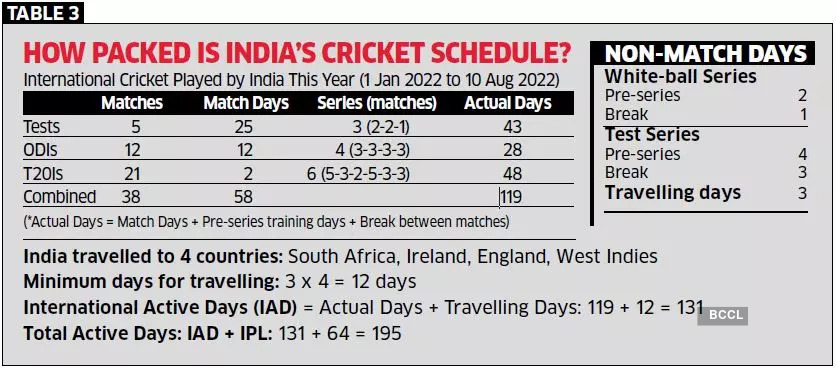

Indian cricket (don’t mistake it with Indian cricketers!) already has 195 ‘active days’, including 64 days of IPL, with only 224 days completed this year (from 1 January 2022 to 10 August 2022) .

A cricketer’s ‘active days’ can be divided into three parts:

- match day

- Training, rest and recovery days

- travel day

But before we go any further, let’s understand how we arrived at this number of 195 active days.

As, and if, you read further, you will realize that the said number is not accurate, certain things had to be assumed, such as the break between two matches, the training days before a series and the travel days. But you will realize that the exact number may not vary much. These approximate numbers were then added to the number of match days, which is also different from the number of matches. For example, a Test match is of five days duration. (But not all Test matches last long.)

The grind begins with the journey. For an overseas series, a team has to gather at one place before flying together and then spend at least a day at their hotel to get rid of jet lag. In total, players need three to four days to be ready to travel abroad and start training.

Any team would need at least two to four days of training to be match-ready. In case of Tests it can be higher as teams also play practice/tour matches. For calculation purposes, let’s give two days for white-ball matches and four days for red-ball cricket.

The third part is the break between matches. While a break may seem like a period of no activity, it is better than nothing. The process of recovery and preparation for the next game involves a lot of activities, sometimes as grueling as the match itself. On average, teams get at least one day’s break between two white-ball games. For Tests, it is at least three days.

For detailed calculations, see Table 3.

No player, however, was active on all days – this is not humanly possible – either with an injury, coming to the rescue for rest or the board-mandated rest. But let’s imagine a cricketer plays all the matches and is active throughout the day, do you see him survive this endless marathon?

While this punitive program affects everyone, the most affected are players of all formats, especially fast bowlers (Boult) and multi-skilled cricketers such as all-rounders (Stokes) and wicketkeepers (de Kock). But Virat Kohli and David Warner are equally impressed by the intensity they display on the field.

The development of a third format, Twenty20, and its spread through franchise leagues have done two things: it has crowded the calendar and brought in never-before-seen money.

This packed cricket schedule is partly aided by the ICC’s push for a bigger event each year, but with a growing number of T20 leagues around the world, players spend some time without missing a series or two. There is no window for

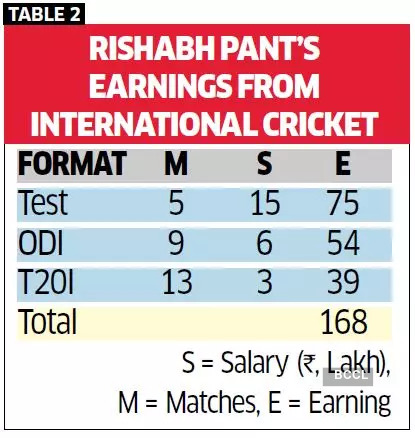

But no player can afford to be ignored in the T20 league. There is a lot of money available to make. This year Rishabh Pant earned 16 crores by playing 14 IPL matches. He has played 27 matches for India so far and has earned only Rs 1.68 crores. Even if you add the Rs 5 crore he gets through the central contract with BCCI, it doesn’t come close to his IPL earnings.

Players are already grappling with the tough choices they will have to make to strike a balance where they can maximize their career earnings, make their country proud and have time to spend with their families. Leaving an international format can bring some balance out of that. For how long, that is a question for the future. Right now, players of all formats are at risk of serious burns.

No comments:

Post a Comment